It is Christmas time here in Minnesota. and I like to catch up on my reading in between snacks and writing my blog.

Reviewing some of the old images, when I was still in recovery, and the dress for success movement was "in" Being playful in nature, the profession of medicine often required a uniform for acceptance. I wore a stethoscope around my neck, with a little koala, always having to deal with others projections AND want not to appear threatening as a tall man, I worked mollify, soften the image impact. Still the tie as a Noose Around my Neck-----and working to be acceptable. One of the symptoms of co dependence, impression management. Funny to look back now from the 21st Century..

In 1986-7- As I was in recovery, having a better acceptance of my self as a two spirited man, Tom N took this photo of me in a sun hat on the Minnesota Prairie - He was a librarian at St Johns University outside of St Cloud back in those days.

Tom N, reading a book to Jesse born in April 1985, I sense this is in 1987 in the St Cloud home Susan and I raised our sons in.

Tom N during an intensive weekend near Palmer Lake Colorado facilitated by Anne Wilson Schaef and others in the Living in Process Community likely in 1986 . We went out with some of the dogs to climb hills. I think one of Anne's dogs was named something like Bubber...and not sure.

I have always enjoyed plants and bird watching and i remember driving west to a Minnesota Prairie Preserve with Tom.....in 1987 here I am in a summer sun hat, expanding my sartorial selections as I was learning more about being two spirited in a Catholic dominated environment raising my kids in Stearns Co, St Cloud. I lost track of Tom N who was still working St John's St Ben's Libraries and his wife was a message therapist at St Cloud Hospital where I was in the family practice staff. Tom is also an alum of Carleton College and I met him and his partner there in the 1990's and recently I met him for a meal in NE Minneapolis where he lives and he updated me on his 2 sons, whom I met so many years ago.

Nate's 5 year birthday party with friends in the St Cloud Home. Covering his ears to focus on blowing out the candles....

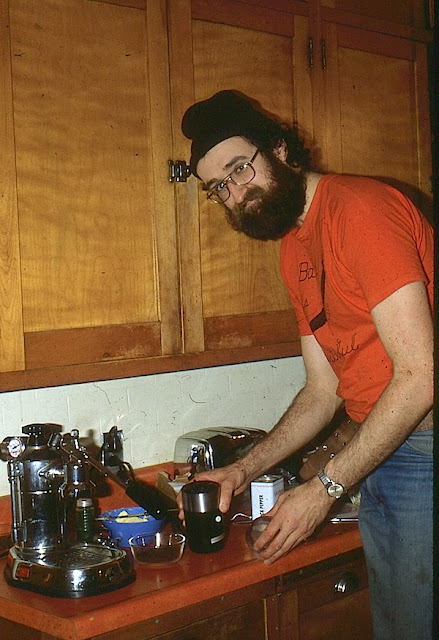

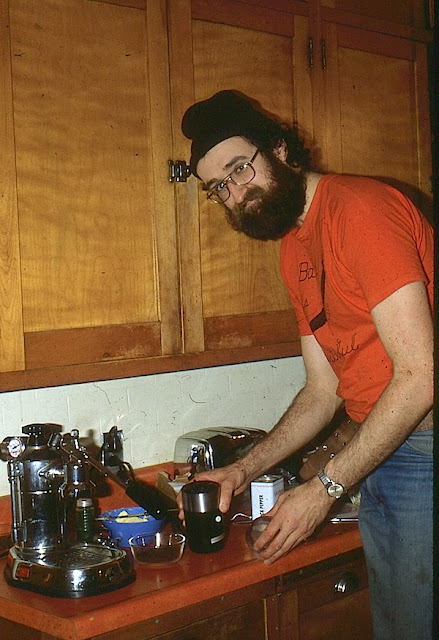

Raised in rural Minnesota to be an outdoors man, I hid my wanting to be attractive to other guys behind this large fuzzy beard.

Making espresso, in the St Cloud Kitchen ca 1981-2 with the Pavoni that Sue and I purchased after our 1980 trip to Italy, being influenced by Italian coffee in places like Firenze, Florence.

Our two sons, Jesse and Nathan around 1986 St Cloud Home

And how I occurred at St Cloud Hospital in the late 1980's, during the time I was the director of the holistic Pain Management Program that included Carol N, Tom N's partner in having his two sons.

And speaking of the St John's Libraries.

Here is a timely article I read this week from the Economist p 63 of the Holiday Double Issue

http://www.economist.com/news/christmas-specials/21683977-catholic-monks-minnesota-are-helping-save-trove-islamic-treasures

THE secret evacuations began at night. Ancient books were packed in small metal shoe-lockers and loaded three or four to a car to reduce the danger to the driver and minimise possible losses. The manuscript-traffickers passed through the checkpoints of their Islamist occupiers on the journey south across the desert from Timbuktu to Bamako. Later, when that road was blocked, they transported their cargo down the Niger river by canoe.

It formed part of a fabulous selection of Islamic literary treasures that had survived floods, heat and invasion over centuries in Timbuktu. But in April 2012 Tuareg rebels had occupied the city. They were soon displaced by the Islamists with whom they had foolishly allied, a group linked to al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. The militants issued edicts to control behaviour, dress and entertainment. Music and football were banned. They destroyed Sufi shrines that had stood for centuries. It was assumed books would be next.

Such fears were not overblown. Islamists had been ruthless with libraries and holy sites in Libya earlier in the year. So in October, the evacuation began. By the time French troops liberated Timbuktu in January 2013 and journalists saw a wing of the city’s grandest new library still smouldering, most of the precious manuscripts had already been spirited away.

The man behind the plan was Abdel Kader Haidara. Born in Timbuktu in 1965, he had grown up surrounded by the treasures: his father, an expert on ancient manuscripts, had inherited a 16th-century Islamic collection and spent his life expanding it. Dr Haidara’s ambitions were even broader. Since 1996 he had run an organisation called SAVAMA (Sauver et Valoriser les Manuscrits). In his office in Bamako, elegantly bound Korans line the bookshelves. Manuscripts lie in stacks, on tables, in corners. He has become their steward.

Dr Haidara, with priceless treasures

Dr Haidara describes Timbuktu as the Sahara’s capital of manuscript

study. But the city was just one of several where north African Islamic

learning flourished at the same time as the European Renaissance. Books

were exchanged as caravans came through Timbuktu and, beginning in the

late 16th century, they were copied there, too. Men who cared about

learning bought or produced libraries full of books about the grammar,

logic and rhetoric of the Koran and its teachings; the positions of

stars; remedies and music. One 16th-century collector, Ahmed Baba, left

behind such a wealth of notation and bibliography that historians call

his period a scholarly zenith

Dr Haidara, with priceless treasures

Dr Haidara describes Timbuktu as the Sahara’s capital of manuscript

study. But the city was just one of several where north African Islamic

learning flourished at the same time as the European Renaissance. Books

were exchanged as caravans came through Timbuktu and, beginning in the

late 16th century, they were copied there, too. Men who cared about

learning bought or produced libraries full of books about the grammar,

logic and rhetoric of the Koran and its teachings; the positions of

stars; remedies and music. One 16th-century collector, Ahmed Baba, left

behind such a wealth of notation and bibliography that historians call

his period a scholarly zenith

Leo Africanus, a Moorish traveller who visited Timbuktu early in the 16th century, said books from abroad traded at higher prices than fabrics, animals or salt. As it fell again and again over the centuries, families held tight to their collections. The city gained a boost from generous donors after independence from France in 1960, when scholars around the world, supported by agencies such as UNESCO, saw its potential as a centre for pan-African historical research. But in 2012, as the Islamists’ grip tightened, Dr Haidara appealed for donations to help evacuate the treasures.

The cars travelled through the night on the bumpy roads of central Mali, their drivers sworn to secrecy. As they arrived in Bamako after more than 12 hours of driving, they were greeted by Dr Haidara, who distributed the documents to loyal friends to be stored. The drivers then turned around to make the trip all over again. Each of the hundreds of volunteers took these risks willingly, and often. More than 370,000 manuscripts now sit in safe houses in Bamako—roughly 95% of the total previously held in Timbuktu, Dr Haidara estimates. They are stored in extra rooms in secret apartments, stacked from floor to ceiling in windowless closets. In one room in Bakodjikoroni, a neighbourhood of Bamako, sit 200 of the metre-long metal cases, glittering with hand-painted filigree, each containing tens or even hundreds of books.

As he looked at the saved manuscripts, Dr Haidara saw another

opportunity that his father could never have imagined: to preserve their

contents in perpetuity. In 2013 he put out a request for help to

digitise them. He received an answer from a monastery on the other side

of the world.

As he looked at the saved manuscripts, Dr Haidara saw another

opportunity that his father could never have imagined: to preserve their

contents in perpetuity. In 2013 he put out a request for help to

digitise them. He received an answer from a monastery on the other side

of the world.

In the basement of the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (HMML) at St John’s, Father Columba flicks on the fluorescent lights. “It’s basically the manuscript culture of Europe in here,” he says, looking at four rows of long metal cabinets containing as many as 100,000 rolls of microfilm. He pulls out the first roll from the first drawer and snaps it into a reader. A white light projects a document on the screen. “This is a Codex,” he says as he rolls through the pages, “Benedictine sermons from the 13th to the 15th century, 880 pages.”

Reviewing some of the old images, when I was still in recovery, and the dress for success movement was "in" Being playful in nature, the profession of medicine often required a uniform for acceptance. I wore a stethoscope around my neck, with a little koala, always having to deal with others projections AND want not to appear threatening as a tall man, I worked mollify, soften the image impact. Still the tie as a Noose Around my Neck-----and working to be acceptable. One of the symptoms of co dependence, impression management. Funny to look back now from the 21st Century..

In 1986-7- As I was in recovery, having a better acceptance of my self as a two spirited man, Tom N took this photo of me in a sun hat on the Minnesota Prairie - He was a librarian at St Johns University outside of St Cloud back in those days.

Tom N, reading a book to Jesse born in April 1985, I sense this is in 1987 in the St Cloud home Susan and I raised our sons in.

I have always enjoyed plants and bird watching and i remember driving west to a Minnesota Prairie Preserve with Tom.....in 1987 here I am in a summer sun hat, expanding my sartorial selections as I was learning more about being two spirited in a Catholic dominated environment raising my kids in Stearns Co, St Cloud. I lost track of Tom N who was still working St John's St Ben's Libraries and his wife was a message therapist at St Cloud Hospital where I was in the family practice staff. Tom is also an alum of Carleton College and I met him and his partner there in the 1990's and recently I met him for a meal in NE Minneapolis where he lives and he updated me on his 2 sons, whom I met so many years ago.

Nate's 5 year birthday party with friends in the St Cloud Home. Covering his ears to focus on blowing out the candles....

Raised in rural Minnesota to be an outdoors man, I hid my wanting to be attractive to other guys behind this large fuzzy beard.

Making espresso, in the St Cloud Kitchen ca 1981-2 with the Pavoni that Sue and I purchased after our 1980 trip to Italy, being influenced by Italian coffee in places like Firenze, Florence.

Our two sons, Jesse and Nathan around 1986 St Cloud Home

And how I occurred at St Cloud Hospital in the late 1980's, during the time I was the director of the holistic Pain Management Program that included Carol N, Tom N's partner in having his two sons.

And speaking of the St John's Libraries.

Here is a timely article I read this week from the Economist p 63 of the Holiday Double Issue

Catholic monks in Minnesota are helping to save a trove of Islamic treasures in Mali

http://www.economist.com/news/christmas-specials/21683977-catholic-monks-minnesota-are-helping-save-trove-islamic-treasures

THE secret evacuations began at night. Ancient books were packed in small metal shoe-lockers and loaded three or four to a car to reduce the danger to the driver and minimise possible losses. The manuscript-traffickers passed through the checkpoints of their Islamist occupiers on the journey south across the desert from Timbuktu to Bamako. Later, when that road was blocked, they transported their cargo down the Niger river by canoe.

It formed part of a fabulous selection of Islamic literary treasures that had survived floods, heat and invasion over centuries in Timbuktu. But in April 2012 Tuareg rebels had occupied the city. They were soon displaced by the Islamists with whom they had foolishly allied, a group linked to al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. The militants issued edicts to control behaviour, dress and entertainment. Music and football were banned. They destroyed Sufi shrines that had stood for centuries. It was assumed books would be next.

Such fears were not overblown. Islamists had been ruthless with libraries and holy sites in Libya earlier in the year. So in October, the evacuation began. By the time French troops liberated Timbuktu in January 2013 and journalists saw a wing of the city’s grandest new library still smouldering, most of the precious manuscripts had already been spirited away.

The man behind the plan was Abdel Kader Haidara. Born in Timbuktu in 1965, he had grown up surrounded by the treasures: his father, an expert on ancient manuscripts, had inherited a 16th-century Islamic collection and spent his life expanding it. Dr Haidara’s ambitions were even broader. Since 1996 he had run an organisation called SAVAMA (Sauver et Valoriser les Manuscrits). In his office in Bamako, elegantly bound Korans line the bookshelves. Manuscripts lie in stacks, on tables, in corners. He has become their steward.

Leo Africanus, a Moorish traveller who visited Timbuktu early in the 16th century, said books from abroad traded at higher prices than fabrics, animals or salt. As it fell again and again over the centuries, families held tight to their collections. The city gained a boost from generous donors after independence from France in 1960, when scholars around the world, supported by agencies such as UNESCO, saw its potential as a centre for pan-African historical research. But in 2012, as the Islamists’ grip tightened, Dr Haidara appealed for donations to help evacuate the treasures.

Turning the page

The evacuation was funded by, among others, the Dutch lottery, the

German government and private donors, to the tune of a reported $1m.

Some $70,000 more was raised through crowdfunding. The details remained

opaque until well after the operation was complete.The cars travelled through the night on the bumpy roads of central Mali, their drivers sworn to secrecy. As they arrived in Bamako after more than 12 hours of driving, they were greeted by Dr Haidara, who distributed the documents to loyal friends to be stored. The drivers then turned around to make the trip all over again. Each of the hundreds of volunteers took these risks willingly, and often. More than 370,000 manuscripts now sit in safe houses in Bamako—roughly 95% of the total previously held in Timbuktu, Dr Haidara estimates. They are stored in extra rooms in secret apartments, stacked from floor to ceiling in windowless closets. In one room in Bakodjikoroni, a neighbourhood of Bamako, sit 200 of the metre-long metal cases, glittering with hand-painted filigree, each containing tens or even hundreds of books.

Somewhere in the frozen north

There can be few places more different from Timbuktu—geographically,

culturally or spiritually—than Collegeville, Minnesota. Swept by winds

as icy as the Saharan ones are baking, it is encrusted with snow for

more than half the year. Towns called St Michael, St Augusta and St

Joseph along the 80-mile road north from Minneapolis hint at the

region’s deep Christian roots. St John’s Abbey is the last turn-off on

the right before St Cloud. When Dr Haidara put out his call for help, it

passed via several intermediaries to a member of the abbey’s board, who

delivered it to Father Columba Stewart. It had reached the right monk.In the basement of the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (HMML) at St John’s, Father Columba flicks on the fluorescent lights. “It’s basically the manuscript culture of Europe in here,” he says, looking at four rows of long metal cabinets containing as many as 100,000 rolls of microfilm. He pulls out the first roll from the first drawer and snaps it into a reader. A white light projects a document on the screen. “This is a Codex,” he says as he rolls through the pages, “Benedictine sermons from the 13th to the 15th century, 880 pages.”

No comments:

Post a Comment